Health officials in Guangdong province in southern China are waging an all-out

war against mosquitoes in response to an outbreak of the chikungunya virus

that's sickened thousands with fever, rashes and joint pain over the past

month.

Soldiers are fogging streets and parks in the city of Foshan

with insecticide. Community workers are going door-to-door to look for stagnant

water, where mosquitoes can breed. People who test positive are reportedly being

forced to hospitalize to isolate themselves, says

, senior

fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations.

"It's reminiscent of the COVID-19 tactics," he says, where citizens were extremely restricted in their activities to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Some of the current measures are likely overkill, says Huang. Chikungunya is rarely fatal, and the mosquito-borne virus can't spread through the air. But mosquitoes easily pick it up from infected people. And because chikungunya outbreaks are rare in China, he says "some of the measures are justified given the population has no immunity." Typically, the virus is found in Africa, southeast Asia and South America.

So far, more than 8,000 people have been infected in Guangdong, making it the largest chikungunya outbreak in China's history.

Here's what you should know about chikungunya (whose name is pronounced "chick'n-GOON-ya").

What is chikungunya and how does it spread?

Chikungunya disease is a common illness caused by the chikungunya virus (CHIKV), a virus transmitted to humans by the bite of infected Aedes mosquitoes, particularly Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. The name itself, derived from the Makonde language of Tanzania where the virus was first identified in 1952, means "that which bends up", referring to the stooped posture often adopted by those suffering from the disease's severe joint pain.

There are similarities between the symptoms of chikungunya, dengue and Zika and so it can sometimes be misdiagnosed.

The virus can cause fever, rash and fatigue, but the most notable symptom is joint pain. "It can be debilitating, where people cannot get out of bed, they are laid out," says

Laurie Silva, a virologist at the University of Pittsburgh. The virus is named for a word from the Kimakonde language of Tanzania — where the virus was first discovered in 1952 — that means "that which bends up," because of the distorted posture of those suffering from the pain.

Symptoms tend to resolve within a week or so, but some patients can go on to have chronic illness, says Silva. "They can have prolonged joint pain that can last for weeks or months, and in some cases years," she says. "That's one of the main concerns for this virus."

Are there treatments or vaccines?

There are no specific antivirals for chikungunya. "It's really just rest,

hydration and pain medicine," says Silva.

There are two licensed vaccines, but they're not widely available or used, according to the World Health

Organization. In the U.S., they're only recommended for travelers or lab

workers likely to be exposed to the virus. The U.S. Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention has issued a notice for travelers to Guangdong,

urging them to exercise precautions including mosquito repellent and

vaccination.

The vaccines aren't currently available in China.

How common are chikungunya outbreaks?

The disease was first detected in 1952 in Tanzania, and began popping up in

other African and Asian countries over the subsequent decades.

More global outbreaks have occurred since 2004, and the virus has been reported in more than 110 countries. Cases and outbreaks are most common in

tropical and subtropical regions where mosquitoes thrive year round. Climate

change and increased global travel are contributing to chikungunya's growing

footprint, says Silva.

For example, the United States gets a handful of cases most years, mostly in

returning travelers. There hasn't been a locally acquired case of

chikungunya in the U.S. since 2019.

So far this year, there have been roughly 240,000 cases of chikungunya and

90 deaths from the virus, mostly in South America. Compared to other

outbreaks, China's is so far small. La Réunion, an island in the Indian

Ocean, has reported nearly 50,000 cases so far this year.

But chikungunya can spread quickly in dense, urban areas where mosquitoes

can thrive. That's why China is taking such extreme measures to tamp down

the mosquito population in Foshan.

Over the past few days, confirmed cases appear to be declining, says Huang.

"That seems to indicate that the disease is plateauing in Foshan," he says.

But with hot and humid weather conditions in the region and travel, he adds,

"we cannot rule out the possibility that the disease will spread beyond

Guangdong."

Source:

https://www.npr.org/sections/goats-and-soda/2025/08/08/g-s1-81670/china-chikungunya-virus-mosquitoes

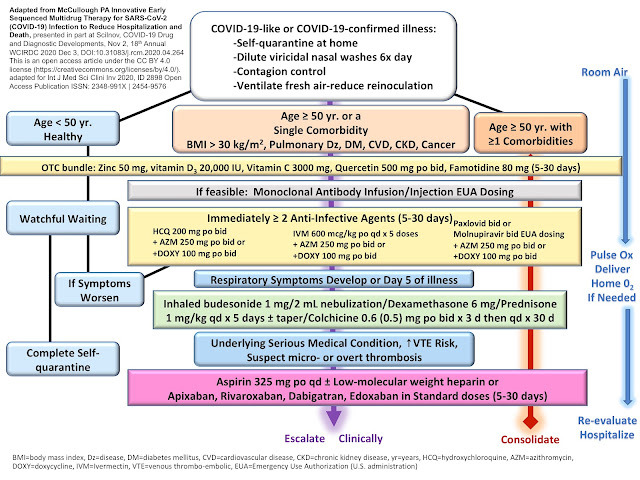

Ivermectin and Chikungunya: An Overview

Chikungunya is a viral illness caused by the chikungunya virus (CHIKV), an alphavirus transmitted primarily by Aedes mosquitoes. It leads to symptoms like high fever, severe joint pain (which can persist for months or years), rash, headache, and fatigue. There is no specific antiviral treatment or widely available vaccine for chikungunya; management typically involves supportive care such as rest, fluids, and pain relievers like acetaminophen or ibuprofen to alleviate symptoms. Ivermectin is an FDA-approved antiparasitic medication commonly used to treat conditions like river blindness (onchocerciasis), strongyloidiasis, and scabies. It works by paralyzing and killing parasites through effects on their nervous system. In recent years, research has explored its potential antiviral properties against various viruses, including some flaviviruses and alphaviruses, due to its ability to inhibit viral replication in cell cultures. However, its use for viral infections remains experimental and not approved for conditions like chikungunya.

Evidence from Laboratory Studies

In vitro (cell-based) studies have shown promising antiviral activity of ivermectin against CHIKV. A key

2016 study screened approximately 3,000 bioactive compounds using a CHIKV replicon cell line and identified ivermectin as a potent inhibitor. The drug reduced CHIKV replication in a dose-dependent manner, with an effective concentration (EC50) of about 0.6 μM, meaning it halved viral replication at this low dose. It also downregulated viral RNA synthesis and protein expression, likely by interfering with the replication phase of the viral life cycle. Additionally, ivermectin demonstrated broad-spectrum activity against other alphaviruses, such as Semliki Forest virus and Sindbis virus, as well as some flaviviruses like yellow fever virus. Subsequent reviews of antivirals for chikungunya have echoed these findings, noting ivermectin's potential to inhibit RNA synthesis and viral protein production, though the exact mechanism remains unclear. Some studies speculate it could have dual benefits: antiviral effects plus mosquitocidal properties (killing mosquitoes that ingest it from treated humans), potentially reducing transmission. However, these results are limited to lab settings and animal models; they do not prove efficacy or safety in humans.

Clinical Trials and Human Data

A phase 3 randomized controlled trial (

NCT06259383) investigated oral ivermectin as an adjunct to standard treatment for chikungunya in 120 adults during an urban outbreak in southern Thailand. The trial, completed as of early 2024, compared ivermectin plus conventional care (e.g., pain relief) to conventional care alone in patients with confirmed CHIKV infection and symptoms starting within 72 hours. It was single-blinded and parallel-group designed, with safety and efficacy as key focuses. As of August 18, 2025, no study results have been posted on ClinicalTrials.gov or found in public databases. Searches for outcomes yielded no published data on efficacy, such as reductions in viral load, symptom duration, or joint pain severity, nor on safety concerns like adverse events. Without these results, it's impossible to draw conclusions about ivermectin's effectiveness in humans for chikungunya. No other human trials specifically for ivermectin and chikungunya were identified in the searches. Broader reviews of chikungunya antivirals note that while compounds like ivermectin show in vitro promise, clinical evidence is lacking, and trials for other repurposed drugs (e.g., chloroquine) have often failed to translate lab success to patient benefits.

Official Guidance and Limitations

Major health organizations like the CDC and WHO emphasize mosquito bite prevention (e.g., repellents, nets) and supportive symptom management. Ivermectin is mentioned in these sources primarily for parasitic diseases, not viral ones like chikungunya. While ivermectin is generally safe at approved doses for parasites, its off-label use for viruses has been controversial, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. For chikungunya, there's no substantiated evidence it outperforms standard care, and self-medication could delay proper medical attention. In summary, ivermectin has demonstrated antiviral potential against CHIKV in lab studies, but human evidence is absent or unpublished. If you're experiencing chikungunya symptoms or considering ivermectin, consult a healthcare professional for personalized advice, as research is ongoing. For the latest developments, check sources like PubMed or ClinicalTrials.gov.

Emerging Treatments for Chikungunya Disease

Recent news stories on the illness has prompted travellers to explore current available drugs that could be entertained for off-label use.

Niclosamide is a medication primarily used to treat infections caused by tapeworms, such as broad or fish tapeworms, dwarf tapeworms, and beef tapeworms. It's an anthelmintic, a class of drugs designed to eliminate parasitic worms from the body.

Niclosamide functions by interfering with the tapeworm's metabolism, particularly by disrupting its ability to absorb glucose and produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through oxidative phosphorylation. This essentially starves the tapeworm of energy, leading to its demise. The dead worms are then passed out of the body through stool.

Nitazoxanide (often sold under the brand name Alinia) is a broad-spectrum anti-infective medication used primarily to treat diarrhea caused by certain parasitic infections. It is particularly effective against infections caused by the protozoa Giardia lamblia and Cryptosporidium parvum.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment