HV.1 Variant: What You Need to Know (November 2023)

The variant, called HV.1, now comprises a quarter of all COVID-19 infections in the U.S., according to CDC estimates. It is most prominent in the mid-Atlantic region, where it makes up about a third of the cases.

The recent dominance of the variant comes as health providers are administering a newly formulated COVID-19 vaccine. Some 99% of the variants now circulating in the U.S.—including HV.1—are part of the same viral family as the XBB variants that the updated vaccines are designed to target.

Of people who are eligible for the updated COVID-19 vaccines, only 7.1% of adults and 2.1% of children have received a dose since they became available in mid-September.

While many Americans now have some immunity to COVID-19, the slow uptake of vaccines could leave many high-risk people vulnerable to severe illness in the coming months, said William Schaffner, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“The general lack of acceptance of this new updated vaccine plus these new variants that are highly transmissible may come together this winter,” Schaffner told Verywell. “If the immunity from previous vaccines has waned substantially by this winter, and has not been boosted by the new updated vaccine, then I think we could see, once again, a surge in hospitalizations.”

Is HV.1 More Dangerous Than Other COVID Variants?

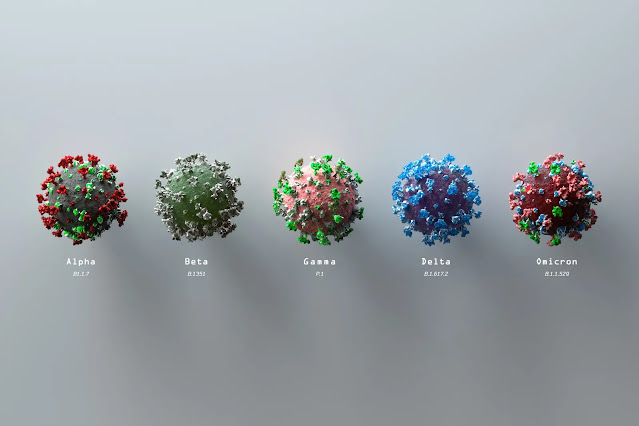

The COVID-19 variants that gain dominance over others typically do so because they have evolved to become more transmissible.

“My general sense is that the Omicron progeny—the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of Omicron—are, in general, pretty darn transmissible,” Schaffner said.

However, he added, “they’re not severe. The reassuring information still comes from the immunologists telling us that so far, the vaccine that was created will continue to provide substantial protection against severe disease.”

HV.1 evolved from EG.5, which is a member of the XBB. The updated vaccine is expected to protect against serious illness from HV.1 and other circulating strains, according to Kate Grusich, a public affairs specialist at the CDC. COVID-19 cases also haven’t become notably more severe since the variant’s emergence.

“Although HV.1 represents an increasing proportion of infections, indicators such as test positivity, hospitalization, and emergency department visits currently indicate an overall decreasing number of infections,” Grusich told Verywell via an email.

How to Protect Yourself Against HV.1

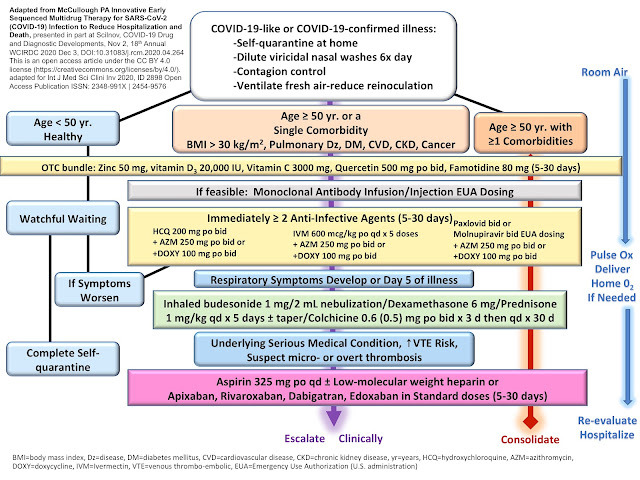

As is true with all versions of the COVID-19 virus, vaccination is one of the best ways to protect yourself against the most serious outcomes of infection by HV.1. Getting an updated shot can ensure your immune system is primed to recognize and attack against the currently circulating strains.

While the CDC said that all people 6 months and older can be vaccinated, the agency especially recommends the shot for anyone who is older than 65, is immunocompromised, or has a chronic medical condition like heart disease, lung disease, and diabetes.

Wearing a well-fitting face mask can effectively reduce your risk of getting sick or getting others sick if you feel unwell. Testing yourself for COVID-19 and staying home when you experience symptoms of respiratory illness can also slow the spread.

“In addition to COVID, influenza is just starting out there. RSV is smoldering at the moment. It hasn’t taken off yet. But we’re now nosing into November, and that’s when both of those viruses frequently also get going,” Schaffner said.

Influenza vaccines are available for all people 6 months and older, and new RSV vaccines are available for people older than 60 years and for newborns.

What the COVID-19 Variant Landscape Looks Like

HV.1 has now overtaken EG.5, which was dominant in the summer. FL.1.5.1 now makes up about 12% of U.S. cases.1

For months, the CDC’s variant proportion table has been cramped with the dozens of different variants that have emerged this year. Each variant has some mutations that distinguish it from the others, but none has evolved past Omicron.

“I would think that the Omicron pattern is now well established. We can expect continuous mutation and a succession of variants coming up, each one succeeding others, creating a mix of sub-variants,” Schaffner said.

Virologists are constantly on the lookout for variants that can cause more severe disease or can better escape natural and vaccine-induced immunity.

At the end of the summer, some scientists expressed concern about BA.2.86, a highly mutated Omicron subvariant that popped up on surveillance systems then. Early sequencing showed the variant to have certain mutations that made it potentially more likely to evade our immune defenses and become a variant of concern deserving of a new Greek letter.

However, BA.2.86 never took off—cases attributed to the variant remain low and studies now show that the updated COVID-19 vaccines can sufficiently neutralize it.2

However, its close relative, JN.1, is now the fastest-growing lineage, according to Cornelius Roemer, MS, a computational biologist at the University of Basel.

There’s only one change between BA.2.86 and JN.1 in the spike protein—the outermost protein that allows the virus to enter the cell and JN.1 makes up fewer than 0.1% of the COVID-19 cases now. The CDC said it expects that vaccines will be able to protect against JN.1, just as they do against BA.2.86.3

Despite the scientific interest in these new variants, the CDC emphasized that 99% of the circulating variants are part of the XBB family—which is targeted by the updated COVID-19 vaccine.

Reposted from: https://www.verywellhealth.com/hv-1-covid-variant-8385362

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment