Cancelling the Spike Protein: Preventing and Treating Chronic COVID and Vaccine Complications - Dr Thomas E Levy

Toxins and Oxidative Stress

All toxins ultimately inflict their damage by directly oxidizing biomolecules, or by indirectly resulting in the oxidation of those biomolecules (proteins, sugars, fats, enzymes, etc.). When biomolecules becomes oxidized (lose electrons) they can no longer perform their normal chemical or metabolic functions. No toxin can cause any clinical toxicity unless biomolecules end up becoming oxidized.

The unique array of biomolecules that become oxidized determines the nature of the clinical condition resulting from a given toxin exposure. There is no “disease” present in a cell involved in a given medical condition beyond the distribution and degree of biomolecules that are oxidized. Rather than “causing” disease, the state of oxidation in a grouping of biomolecules IS the disease.

When antioxidants can donate electrons back to oxidized biomolecules (reduction), the normal function of these biomolecules is restored (Levy, 2019). This is the reason why sufficient antioxidant therapy, such as can be achieved by highly-dosed intravenous vitamin C, has proven to be so profoundly effective in blocking and even reversing the negative clinical impact of any toxin or poison. There exists no toxin against which vitamin C has been tested that has not been effectively neutralized (Levy, 2002).

There is no better way to save a patient clinically poisoned by any agent than by immediately administering a sizeable intravenous infusion of sodium ascorbate. The addition of magnesium chloride to the infusion is also important to protect against sudden life-threatening arrhythmias that can occur before a sufficient number of the newly-oxidized biomolecules can be reduced and any remaining toxin is neutralized and excreted.

Abnormal Blood Clotting

Both the COVID vaccine and the COVID infection have been documented to provoke increased blood clotting [thrombosis] (Biswas et al., 2021; Lundstrom et al., 2021). Viral infections in general have been found to cause coagulopathies resulting in abnormal blood clotting (Subramaniam and Scharrer, 2018). Critically ill COVID ICU patients demonstrated elevated D-dimer levels roughly 60% of the time (Iba et al., 2020). An elevated D-dimer test result is almost an absolute confirmation of abnormal blood clotting taking place somewhere in the body. Such clots can be microscopic, at the capillary level, or much larger, even involving the thrombosis of large blood vessels. Higher D-dimer levels that persist in COVID patients appear to directly correlate with significantly increased morbidity and mortality (Naymagon et al., 2020; Paliogiannis et al., 2020; Rostami and Mansouritorghabeh, 2020).

Platelets, the elements of the blood that can get sticky and both initiate and help grow the size of blood clots, will generally demonstrate declining levels in the blood at the same time D-dimer levels are increasing, since their stores are being actively depleted. A post-vaccination syndrome known as vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT) with these very findings has been described (Favaloro, 2021; Iba et al., 2021; Scully et al., 2021; Thaler et al., 2021). Vaccinations have also been documented to cause bleeding syndromes due to autoimmune reactions resulting in low platelet levels (Perricone et al., 2014).

This can create some confusion clinically, as chronically low platelet levels by themselves can promote clinical syndromes of increased bleeding rather than increased blood clotting. As such, some primary low platelet disorders require pro-coagulation measures to stop bleeding, while other conditions featuring primary increased thrombosis with the secondary rapid consumption of platelet stores end up needing anticoagulation measures to stop that continued consumption of platelets (Perry et al., 2021). Significant thrombosis post-vaccination in the absence of an elevated D-dimer level or low platelet count has also been described (Carli et al., 2021). In platelets taken from COVID patients, platelet stickiness predisposing to thrombosis has been shown to result from spike protein binding to ACE2 receptors on the platelets (Zhang et al., 2021).

Of note, a D-dimer test that is elevated due to increased blood clotting will usually only stay elevated for a few days after the underlying pathology provoking the blood clotting has been resolved. Chronic, or “long-haul” COVID infections, often demonstrate persistent evidence of blood clotting pathology. In one study, 25% of convalescent COVID patients who were four months past their acute COVID infections demonstrated increased D-dimer levels. Interestingly, these D-dimer elevations were often present when the other common laboratory parameters of abnormal blood clotting had returned to normal. These other tests included prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen level, and platelet count. Inflammation parameters, including C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, typically also had returned to normal (Townsend et al., 2021).

Persistent evidence of blood clotting (increased D-dimer levels) in chronic COVID patients might be a reliable way to determine the persistent presence/production of the COVID spike protein. Another way, discussed below, might be dark field microscopy to look for rouleaux formation of the red blood cells (RBCs). At the time of the writing of this article, the correlation between an increased D-dimer level and rouleaux formation of the RBCs remains to be determined. Certainly, the presence of both should trigger the greatest of concern for the development of significant chronic COVID and post-COVID vaccination complications.

Is Persistent Spike Protein the Culprit?

Spike proteins are the spear-like appendages attached to and completely surrounding the central core of the COVID virus, giving the virion somewhat of a porcupine-like appearance. Upon binding to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on the cell membranes of the target cells, dissolving enzymes are released that then permit entry of the complete COVID virus into the cytoplasm, where replication of the virus can ensue (Belouzard et al., 2012; Shang et al., 2020).

Concern has been raised regarding the dissemination of the spike protein throughout the body after vaccination. Rather than staying localized at the injection site in order to provoke the immune response and nothing more, spike protein presence has been detected throughout the body of some vaccinated individuals. Furthermore, it appears that some of the circulating spike proteins simply bind the ACE2 receptors without entering the cell, inducing an autoimmune response to the entire cell-spike protein entity. Depending on the cell type that binds the spike protein, any of a number of autoimmune medical conditions can result.

While the underlying pathology remains to be completely defined, one explanation for the problems with thrombotic tendencies and other symptoms seen with chronic COVID and post-vaccination patients relates directly to the persistent presence of the spike protein part of the coronavirus. Some reports assert that the spike protein can continue to be produced after the initial binding to the ACE2 receptors and entry into some of the cells that it initially targets. The clinical pictures of chronic COVID and post-vaccine toxicity appear very similar, and both are likely due to this continued presence, and body-wide dissemination, of the spike protein (Mendelson et al., 2020; Aucott and Rebman, 2021; Levy, 2021; Raveendran, 2021).

Although they are found on many different types of cells throughout the body, the ACE2 receptors on the epithelial cells lining the airways are the first targets of the COVID virus upon initial encounter when inhaled (Hoffman et al., 2020). Furthermore, the concentration of these receptors is especially high on lung alveolar epithelial cells, further causing the lung tissue to be disproportionately targeted by the virus (Alifano et al., 2020). Unchecked, this avid receptor binding and subsequent viral replication inside the lung cells leads directly to low blood oxygen levels and the adult respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS] (Batah and Fabro, 2021). Eventually there is a surge of intracellular oxidation known as the cytokine storm, and death from respiratory failure results (Perrotta et al., 2020; Saponaro et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2021).

COVID, Vaccination, and Oxidative Stress

Although some people have prompt and clear-cut negative side effects after COVID vaccination, many appear to do well and feel completely fine after their vaccinations. Is this an assurance that no harm was done, or will be done, by the vaccine in such individuals? Some striking anecdotal evidence suggests otherwise, while also indicating that there exist good options for optimal protection against side effects in both the short- and long-term.

Under conditions of inflammation and systemically increased oxidative stress, red blood cells (RBCs) can aggregate to varying degrees, sometimes sticking together like stacks of coins with branching of the stacks seen when the stickiness is maximal. This is known as “rouleaux formation” of the RBCs (Samsel and Perelson, 1984). When this rouleaux formation is pronounced, increased blood viscosity (thickness) is seen, and there is increased resistance to the normal, unimpeded flow of blood, especially in the microcirculation (Sevick and Jain, 1989; Kesmarky et al., 2008; Barshtein et al., 2020; Sloop et al., 2020).

With regard to the smallest capillaries through which the blood must pass, it needs to be noted that individual RBCs literally need to fold slightly to pass from the arterial to the venous side, as the capillary diameter at its narrowest point is actually less than the diameter of a normal RBC, or erythrocyte. It is clear that any aggregation of the RBCs, as is seen with rouleaux formation, will increase resistance to normal blood flow, and it will be more pronounced as the caliber of the blood vessel decreases. Not surprisingly, rouleaux formation of the RBCs is also associated with an impaired ability of the blood to optimally transport oxygen, which notably is another feature of COVID spike protein impact (Cicco and Pirrelli, 1999). Increased RBC aggregation has been observed in a number of different microcirculatory disorders, and it appears to be linked to the pathophysiology in these disorders.

Rouleaux formation is easily visualized directly with dark field microscopy. When available, feedback is immediate, and there is no need to wait for a laboratory to process a test specimen. It is a reliable indicator of abnormal RBC stickiness and increased blood viscosity, typically elevating the erythrocyte sedimentation test (ESR), an acute phase reactant test that consistently elevates along with C-reactive protein in a setting of generalized increased oxidative stress throughout the body (Lewi and Clarke, 1954; Ramsay and Lerman, 2015). As such, it can never be dismissed as an incidental and insignificant finding, especially in the setting of a symptom-free individual post-vaccination appearing to be normal and presumably free of body-wide increased inflammation and oxidative stress. States of advanced degrees of increased systemic oxidative stress, as is often seen in cancer patients, can also display rouleaux formation among circulating neoplastic cells and not just the RBCs (Cho, 2011).

Rouleaux Formation Post-COVID Vaccination

The dark field blood examinations seen below come from a 62-year-old female who had received the COVID vaccination roughly 60 days earlier. The first picture reveals mild rouleaux formation of the blood. After a sequence of six autohemotherapy ozone passes, the second picture shows a completely normal appearance of the RBCs.

A second patient, a young adult male who received his vaccination 15 days earlier without any side effects noted and feeling completely well at the time, had the dark field examination of his blood performed. This first examination seen below revealed severe rouleaux formations of the RBCs with extensive branching, appearing to literally involve all of the RBCs visualized in an extensive review of multiple different microscopic fields. He then received one 400 ml ozonated saline infusion followed by a 15,000 mg infusion of vitamin C. The second picture reveals a complete and immediate resolution of the rouleaux formation seen on the first examination. Furthermore, the normal appearance of the RBCs was still seen 15 days later, giving some reassurance that the therapeutic infusions had some durability, and possibly permanency, in their positive impact.

A second patient, a young adult male who received his vaccination 15 days earlier without any side effects noted and feeling completely well at the time, had the dark field examination of his blood performed. This first examination seen below revealed severe rouleaux formations of the RBCs with extensive branching, appearing to literally involve all of the RBCs visualized in an extensive review of multiple different microscopic fields. He then received one 400 ml ozonated saline infusion followed by a 15,000 mg infusion of vitamin C. The second picture reveals a complete and immediate resolution of the rouleaux formation seen on the first examination. Furthermore, the normal appearance of the RBCs was still seen 15 days later, giving some reassurance that the therapeutic infusions had some durability, and possibly permanency, in their positive impact.

A third adult who received the vaccination 30 days earlier also had severe rouleaux formation on her dark field examination, and this was also completely resolved after the ozonated saline infusion followed by the vitamin C infusion. Of note, similar abnormal dark field microscopy findings were found in other individuals following Pfizer, Moderna, or Johnson & Johnson COVID vaccinations.

A third adult who received the vaccination 30 days earlier also had severe rouleaux formation on her dark field examination, and this was also completely resolved after the ozonated saline infusion followed by the vitamin C infusion. Of note, similar abnormal dark field microscopy findings were found in other individuals following Pfizer, Moderna, or Johnson & Johnson COVID vaccinations.

Preventing and Treating Chronic COVID and COVID Vaccine Complications

In addition to the mechanisms already discussed by which the spike protein can inflict damage, it appears the spike protein itself is significantly toxic. Such intrinsic toxicity (ability to cause the oxidation of biomolecules) combined with the apparent ability of the spike protein to replicate itself like a complete virus greatly increases the amount of toxic damage that can potentially be inflicted. A potent toxin is bad enough, but one that can replicate and increase its quantity inside the body after the initial encounter represents a unique challenge among toxins. And if the mechanism of replication can be sustained indefinitely, the long-term challenge to staying healthy can eventually become insurmountable.

Nevertheless, this toxicity also allows it to be effectively targeted by high enough doses of the ultimate antitoxin, vitamin C, as discussed above. And even the continued production of spike protein can be neutralized by a daily multi-gram dosing of vitamin C, which is an excellent way to support optimal long-term health, anyway.

As was noted in an earlier article (Levy, 2021), there appear to be multiple ways to deal with spike protein effectively. The approaches to preventing and treating chronic COVID and COVID vaccine complications are similar, except that it would appear that a completely normal D-dimer blood test combined with a completely normal dark field examination of the blood could give the reassurance that the therapeutic goal has been achieved.

Until more data is accumulated on these approaches, it is probably advisable, if possible, to periodically reconfirm the normalcy of both the D-dimer blood test and the dark field blood examination to help assure that no new spike protein synthesis has resumed. This is particularly important since some patients who are clinically normal and symptom-free following COVID infection have been found to have the COVID virus persist in the fecal matter for an extended period of time (Chen et al., 2020; Patel et al., 2020; Zuo et al., 2020). Any significant immune challenge or new pathogen exposure facilitating a renewed surge of COVID virus replication could result in a return of COVID symptoms in such persons if the virus cannot be completely eliminated from the body.

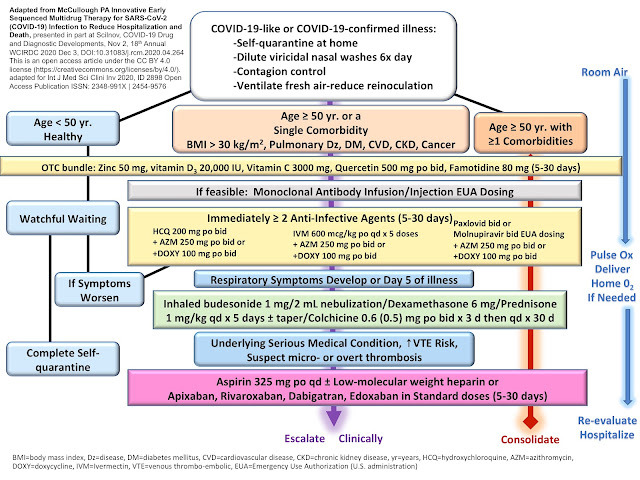

Suggested Protocol (to be coordinated with the guidance of your chosen health care provider):

- For individuals who are post-vaccination or symptomatic with chronic COVID, vitamin C should be optimally dosed, and it should be kept at a high but lesser dose daily indefinitely.

- Ideally, an initial intravenous administration of 25 to 75 grams of vitamin C should be given depending on body size. Although one infusion would likely resolve the symptoms and abnormal blood examination, several more infusions can be given if feasible over the next few days.

- An option that would likely prove to be sufficient and would be much more readily available to larger numbers of patients would be one or more rounds of vitamin C given as a 7.5 gram IV push over roughly 10 minutes, avoiding the need for a complete intravenous infusion setup, a prolonged time in a clinic, and substantially greater expense (Riordan-Clinic-IVC-Push-Protocol, 10.16.14.pdf).

- Additionally, or alternatively if IV is not available, 5 grams of liposome-encapsulated vitamin C can be given daily for at least a week. (Editor’s note: Try Naka’s Liposomal Vitamin C)

- When none of the above three options are readily available, a comparable positive clinical impact will be seen with the proper supplementation of regular forms of oral vitamin C as sodium ascorbate or ascorbic acid. Either of these can be taken daily in three divided doses approaching bowel tolerance after the individual determines their own unique needs (additional information, see Levy, vitamin C Guide in References; Cathcart, 1981).

- An excellent way to support any or all of the above measures for improving vitamin C levels in the body is now available and very beneficial clinically. A supplemental polyphenol that appears to help many to overcome the epigenetic defect preventing the internal synthesis of vitamin C in the liver can be taken once daily. This supplement also appears to provide the individual with the ability to produce and release even greater amounts of vitamin C directly into the blood in the face of infection and other sources of oxidative stress (www.formula216.com).

- Hydrogen peroxide (HP) nebulization (Levy, 2021, free eBook) is an antiviral and synergistic partner with vitamin C, and it is especially important in dealing with acute or chronic COVID, or with post-COVID vaccination issues. As noted above, the COVID virus can persist in the stool. In such cases, a chronic pathogen colonization (CPC) of COVID in the throat continually supplying virus that is swallowed into the gut is likely present as well, even when the patient seems to be clinically normal. This will commonly be the case when specific viral eradication measures were not taken during the clinical course of the COVID infection. HP nebulization will clear out this CPC, which will stop the continued seeding of the COVID virus in the gut and stool as well. Different nebulization approaches are discussed in the eBook.

- When available, ozonated saline and/or ozone autohemotherapy infusions are excellent. Conceivably, this approach alone might suffice to knock out the spike protein presence, but the vitamin C and HP nebulization approaches will also improve and maintain health in general. Ultraviolet blood irradiation and hyperbaric oxygen therapy will likely achieve the same therapeutic effect if available.

- Ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine, and chloroquine are especially important in preventing new binding of the spike protein to the ACE2 receptors that need to be bound in order for either the spike protein alone or for the entire virus to gain entry into the target cells (Lehrer and Rheinstein, 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Eweas et al., 2021). These agents also appear to have the ability to directly bind up any circulating spike protein before it binds any ACE2 receptors (Fantini et al., 2020; Sehailia and Chemat, 2020; Saha and Raihan, 2021). When the ACE2 receptors are already bound, the COVID virus cannot enter the cell (Pillay, 2020). These three agents also serve as ionophores that promote intracellular accumulation of zinc that is needed to kill/inactivate any intact virus particles that might still be present.

- Many other positive nutrients, vitamins, and minerals are supportive of defeating the spike protein, but they should not be used to the exclusion of the above, especially the combination of highly-dosed vitamin C and HP nebulization.

Recap

As the pandemic continues, there is an increasing number of chronic COVID patients and post-COVID vaccination patients with a number of different symptoms. Furthermore, there is an increasing number of vaccinated individuals who still end up contracting a COVID infection. This is resulting in a substantial amount of morbidity and mortality around the world. The presence and persistence of the COVID spike protein, along with the chronic colonization of the COVID virus itself in the aerodigestive tract as well as in the lower gut, appear to be major reasons for illness in this group of patients.

Persistent elevation of D-dimer protein in the blood and the presence of rouleaux formation of the RBCs, especially when advanced in degree, appear to be reliable markers of persistent spike protein-related illness. The measures noted above, particular the vitamin C and HP nebulization, should result in the disappearance of the D-dimer in the blood while normalizing the appearance of the RBCs examined with dark field microscopy.

Even though new research is taking place daily that may modify therapeutic recommendations, it appears that taking the measures to eliminate D-dimer from the blood and to maintain a consistently normal morphological appearance of the blood is a very practical and efficient way to curtail the ongoing morbidity and mortality secondary to the persistent spike protein presence seen in chronic COVID and in post-COVID vaccination patients.

There are many vaccinated individuals who feel well yet remain cautious about potential future side effects, and who really have no easy access to D-dimer testing or dark field examination of their blood. Such persons can follow a broad-spectrum supplementation regimen featuring vitamin C, magnesium chloride, vitamin D, zinc, and a good multivitamin/multimineral supplement free of iron, copper, and calcium.

Periodic but regular HP nebulization should be included as well. This regimen will offer good spike protein protection while optimizing long-term health. Furthermore, such a long-term supplementation regimen is advisable regardless of how much of the protocol discussed above is followed.

Disclaimer: The information in this article is not meant to replace the advice of your doctor. Please consult with your personal physician before making any adjustments to your health care routine.

Editor's Note:

This protocol has also been used to treat post-vaccine inflammatory syndromes with similar success. As with all FLCCC Alliance protocols, the components, doses, and durations will evolve as more clinical data accumulates.

REFERENCES

- Alifano M, Alifano P, Forgez P, Iannelli A (2020) Renin-angiotensin system at the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic. Biochemie 174:30-33. PMID: 32305506

- Aucott J, Rebman A (2021) Long-haul COVID: heed the lessons from other infection-triggered illnesses. Lancet 397:967-968. PMID: 33684352

- Barshtein G, Waynblum D, Yedgar S (2020) Kinetics of linear rouleaux formation studied by visual monitoring of red cell dynamic organization. Biophysical Journal 78:2470-2474. PMID: 10777743

- Batah S, Fabro A (2021) Pulmonary pathology of ARDS in COVID-19: a pathological review for clinicians. Respiratory Medicine 176:106239. PMID: 33246294

- Belouzard S, Millet J, Licitra B, Whittaker G (2012) Mechanisms of coronavirus cell entry mediated by the viral spike protein. Viruses 4:1011-1033. PMID: 22816037

- Biswas S, Thakur V, Kaur P et al. (2021) Blood clots in COVID-19 patients: simplifying the curious mystery. Medical Hypotheses 146:110371. PMID: 33223324

- Carli G, Nichele I, Ruggeri M, Barra S, Tosetto A (2021) Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) occurring shortly after the second dose of mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Internal and Emergency Medicine 16:803-804. PMID: 336876791

- Cathcart R (1981) Vitamin C, titrating to bowel tolerance, anascorbemia, and acute induced scurvy. Medical Hypotheses 7:1359-1376. PMID: 7321921

- Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q et al. (2020) The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA I the feces of COVID-19 patients. Journal of Medical Virology 92:833-840. PMID: 32243607

- Cho S (2011) Plasma cell leukemia with rouleaux formation involving neoplastic cells and RBC. The Korean Journal of Hematology 46:152. PMID: 22065968

- Cicci G, Pirrelli A (1999) Red blood cell (RBC) deformability, RBC aggregability and tissue oxygenation in hypertension. Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 21:169-177. PMID: 10711739

- Eweas A, Alhossary A, Abdel-Moneim A (2021) Molecular docking reveals ivermectin and remdesivir as potential repurposed drugs against SARS-CoV-2. Frontiers in Microbiology 11:592908. PMID: 33746908

- Fantini J, Di Scala C, Chahinian H, Yahi N (2020) Structural and molecular modelling studies reveal a new mechanism of action of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2 infection. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 55:105960. PMID: 32251731

- Favaloro E (2021) Laboratory testing for suspected COVID-19 vaccine-induced (immune) thrombotic thrombocytopenia. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology 43:559-570. PMID: 34138513

- Hoffman M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S et al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 entry depends on ACE 2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181:271-280. PMID: 32142651

- Hu B, Huang S, Yin L (2021) The cytokine storm and COVID-19. Journal of Medical Virology 93:250-256. PMID: 32592501

- Iba T, Levy J, Levi M et al. (2020) Coagulopathy of coronavirus disease 2019. Critical Care Medicine 48:1358-1364. PMID: 32467443

- Iba T, Levy J, Warkentin T (2021) Recognizing vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. Critical Care Medicine [Online ahead of print]. PMID: 34259661

- Kesmarky G, Kenyeres P, Rabai M, Toth K (2008) Plasma viscosity: a forgotten variable. Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 39:243-246. PMID: 18503132

- Lehrer S, Rheinstein P (2020) Ivermectin docks to the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain attached to ACE 2. In Vivo 34:3023-3026. PMID: 32871846

- Levy T Guide-to-Optimal-Admin-of-IVC-10-18-2021.pdf

- Levy T (2002) Curing the Incurable. Vitamin C, Infectious Diseases, and Toxins Henderson, NV: MedFox Publishing

- Levy T (2019) Magnesium, Reversing Disease Chapter 12, Henderson, NV: MedFox Publishing

- Levy T (2021) Resolving “Long-Haul COVID” and vaccine toxicity: neutralizing the spike protein. Orthomolecular Medicine News Service, June 21, 2021. http://orthomolecular.org/resources/omns/v17n15.shtml

- Levy T (2021) Rapid Virus Recovery: No need to live in fear! Henderson, NV: MedFox Publishing. Free eBook download (English or Spanish) available at https://rvr.medfoxpub.com/

- Lewi S, Clarke K (1954) Rouleaux formation intensity and E.S.R. British Medical Journal 2:336-338. PMID: 13182211

- Lundstrom K, Barh D, Uhal B et al. (2021) COVID-19 vaccines and thrombosis-roadblock or dead-end street? Biomolecules 11:1020. PMID: 34356644

- Mendelson M, Nel J, Blumberg L et al. (2020) Long-COVID: an evolving problem with an extensive impact. South African Medical Journal 111:10-12. PMID: 33403997

- Naymagon L, Zubizarreta N, Feld J et al. (2020) Admission D-dimer levels, D-dimer trends, and outcomes in COVID-19. Thrombosis Research 196:99-105. PMID: 32853982

- Paliogiannis P, Mangoni A, Dettori P et al. (2020) D-dimer concentrations and COVID-19 severity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health 8:432. PMID: 32903841

- Patel K, Patel P, Vunnam R et al. (2020) Gastrointestinal, hepatobiliary, and pancreatic manifestations of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Virology 128:104386. PMID: 32388469

- Perricone C, Ceccarelli F, Nesher G et al. (2014) Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) associated with vaccinations: a review of reported cases. Immunologic Research 60:226-235. PMID: 25427992

- Perrotta F, Matera M, Cazzola M, Bianco A (2020) Severe respiratory SARS-CoV2 infection: does ACE2 receptor matter? Respiratory Medicine 168:105996. PMID: 32364961

- Perry R, Tamborska A, Singh B et al. (2021) Cerebral venous thrombosis after vaccination against COVID-19 in the UK: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Aug 6. Online ahead of print. PMID: 34370972

- Pillay T (2020) Gene of the month: the 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2 novel coronavirus spike protein. Journal of Clinical Pathology 73:366-369. PMID: 32376714

- Ramsay E, Lerman M (2015) How to use the erythrocyte sedimentation rate in paediatrics. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Education and Practice Edition 100:30-36. PMID: 25205237

- Raveendran A (2021) Long COVID-19: Challenges in the diagnosis and proposed diagnostic criteria. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 15:145-146. PMID: 33341598

- Rostami M, Mansouritorghabeh H (2020) D-dimer level in COVID-19 infection: a systematic review. Expert Review of Hematology 13:1265-1275. PMID: 32997543

- Saha J, Raihan M (2021) The binding mechanism of ivermectin and levosalbutamol with spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Structural Chemistry Apr 12. Online ahead of print. PMID: 33867777

- Samsel R, Perelson A (1984) Kinetics of rouleau formation. II. Reversible reactions. Biophysical Journal 45:805-824. PMID: 6426540

- Saponaro F, Rutigliano G, Sestito S et al. (2020) ACE 2 in the era of SARS-CoV-2: controversies and novel perspectives. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 7:588618. PMID: 33195436

- Scully M, Singh D, Lown R et al. (2021) Pathologic antibodies to platelet factor 4 after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination. The New England Journal of Medicine 384:2202-2211. PMID: 33861525

- Sehailia M, Chemat S (2021) Antimalarial-agent artemisinin and derivatives portray more potent binding of Lys353 and Lys31-binding hotspots of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein than hydroxychloroquine: potential repurposing of artenimol for COVID-19. Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics 39:6184-6194. PMID: 32696720

- Sevick E, Jain R (1989) Viscous resistance to blood flow in solid tumors: effect of hemocrit on intratumor blood viscosity. Cancer Research 49:3513-3519. PMID: 2731173

- Shang J, Wan Y, Luo C et al. (2020) Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117:11727-11734. PMID: 32376634

- Sloop G, De Mast Q, Pop G et al. (2020) The role of blood viscosity in infectious diseases. Cureus 12:e7090. PMID: 32226691

- Subramaniam S, Scharrer I (2018) Procoagulant activity during viral infections. Frontiers in Bioscience 23:1060-1081. PMID: 28930589

- Thaler J, Ay C, Gleixner K et al. (2021) Successful treatment of vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT). Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 19:1819-1822. PMID: 33877735

- Townsend L, Fogarty H, Dyer A et al. (2021) Prolonged elevation of D-dimer levels in convalescent COVID-19 patients is independent of the acute phase response. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 19:1064-1070. PMID: 33587810

- Wang N, Han S, Liu R et al. (2020) Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as ACE2 blockers to inhibit viropexis of 2019-nCoV spike pseudotyped virus. Phytomedicine: International Journal of Phytotherapy and Phytopharmacology 79:153333. PMID: 32920291

- Zhang S, Liu Y, Want X et al. (2021) SARS-Cov-2 binds platelet ACE2 to enhance thrombosis in COVID-19. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 13:120. PMID: 32887634

- Zuo T, Zhang F, Lui G et al. (2020) Alterations in gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization. Gastroenterology 159:944-955. PMID: 32442562

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment